While we’re living through an epidemic that is unprecedented in our lifetimes, CLP has closed in the past in a similar situation. The library was closed for two weeks in 1918 during the influenza pandemic that swept the state in September and October of that year. The library’s 1918 annual report makes a note of this, but doesn’t provide a lot of other details. After all, the overwhelming news of 1918 was World War I and its eventual end.

There are numerous sources about the 1918 pandemic referred to as the Spanish Flu (see the end of this post for recommendations), so I’ll stay focused on what happened here in Pittsburgh.

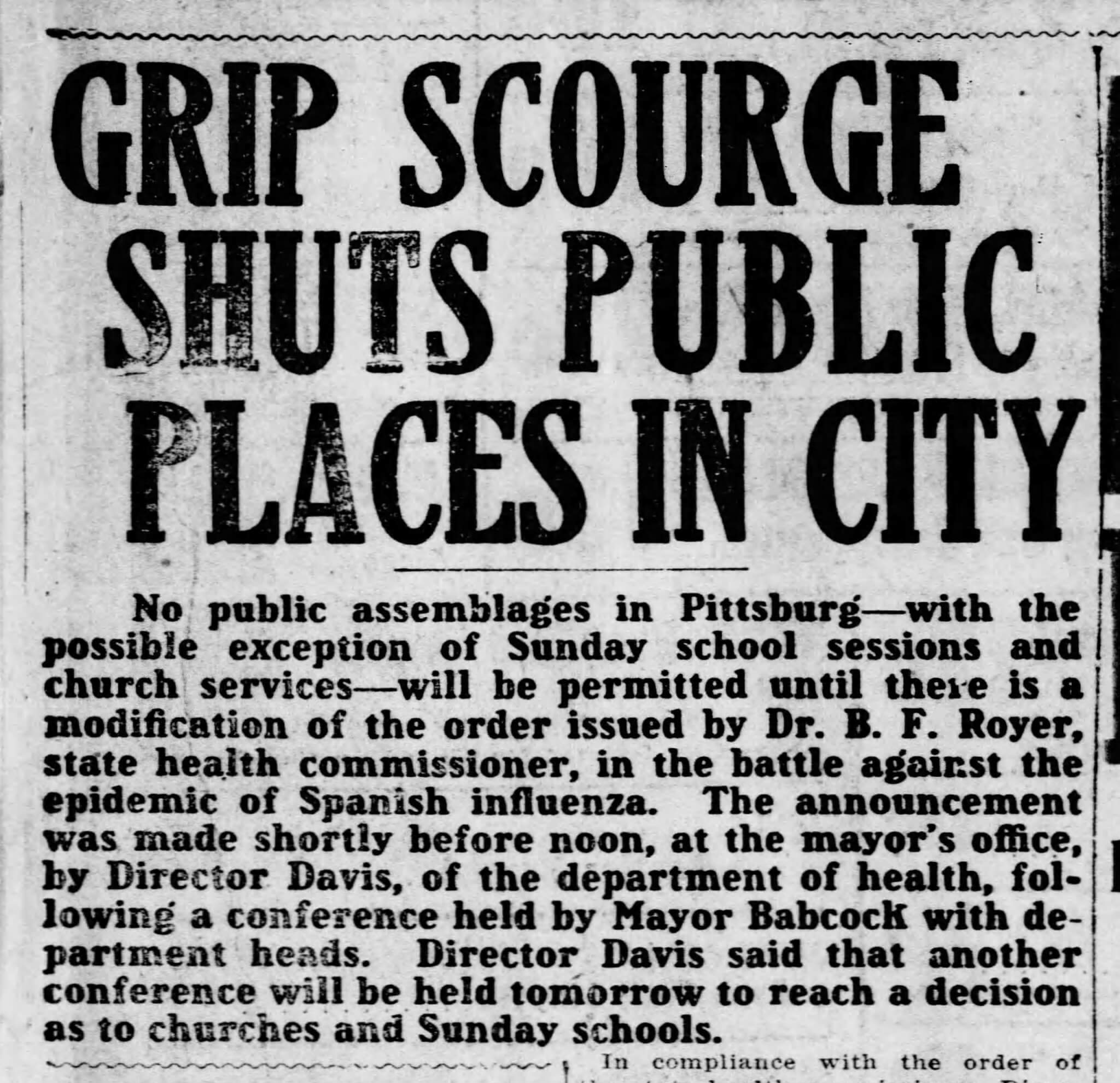

In Pennsylvania, the flu hit Philadelphia first in mid-September, then started traveling west. A couple of weeks later, on October 4, two things happened. Pittsburgh had what is considered its first official flu-related death, and Acting State Health Commissioner B. Franklin Dwyer ordered the closure of all places of amusement in the state. Here in Pittsburgh, that meant that 1,400 saloons, 165 movie theaters, and all of the theaters and vaudeville houses were shuttered. The order also cancelled all college football games, banned public funerals and visiting the sick unless they were near death. While the next day, the Pittsburgh Press declared, “No epidemic here,” that wouldn’t last long.

The next week saw closure of even more public spaces – swimming pools, billiard parlors, churches and schools. While the medical community was still unsure what caused the flu, they knew that people gathering in large groups, in enclosed spaces would definitely spread it. Notably, and remember this for later, liquor wholesalers were closed on October 8, causing a public outcry.

Not surprisingly, closure of so many gathering places lead to an increase in library users. In its 1918 annual report, the Homewood Branch reported, “This fall, we had a very noticeable increase in attendance on the nights when theatres and movies were closed by the influenza.”

While the newspapers announced that Wiliam H. Davis, head of the city health department, ordered the libraries closed on October 24, an October 26 letter that appears to be from Dr. John H. Leete* the library director, dictated only that circulation of books and pamphlets would stop, the children’s rooms would be closed, that anyone who seemed to have a cold would be banned and that limited in-person consultations would be allowed in the branches based on having a reasonable number of people in the space.

As the epidemic dragged on to early November, tensions were rising between Dwyer and Mayor Edward V. Babock. After initially following the state’s orders to close businesses, Babcock soon started to advocate for a return to business as usual, even as hospitals were filled to capacity, temporary hospitals were hastily cobbled together, and services such as mail and the fire department essentially stopped because so many workers were sick. October 29 saw the highest number of flu deaths so far with 176 on that day.

When Royer announced that churches could re-open on November 6, and the ban on businesses would be lifted on Saturday, November 9, Babcock quickly declared that businesses, specifically saloons and movie theaters, should feel free to reopen on Sunday, November 3, despite having no authority to change state rules. This prompted Royer to accuse the mayor of being in the liquor wholesalers’ pockets since they were losing so much money.

Even within library administration, there was dissent. Samuel Harden Church, president of the board of directors wrote to Dr. John H. Leete on November 4 that the libraries should remain closed even after the mayor’s declaration. “My idea is that as long as the circulating departments of the library are closed, we should not be too precipitate in opening them. There is bitter controversy between the state and city authorities over the influenza question and we should play on the safe side by doing nothing and saying nothing until this controversy has abated in its bitterness,” he wrote.

Leete* presented lengthy and detailed objections, arguing that there was no evidence books transmitted disease and that opting to remain closed might be interpreted as flouting city orders to re-open, jeopardizing future city funding. While the draft we have is undated, it directly responds to Church’s November 4 directive to keep the doors closed. Since writers could exchange multiple letters per day within the city, this likely dates from either November 4 or 5.

The library’s annual report for 1918 indicates the library was closed for two weeks, meaning at least the Central branch (now referred to as Main in Oakland) resumed some operations on or around Thursday, Nov. 7. The archives haven’t yet given us the exact date thanks to Church’s permission or a memo, and the newspapers didn’t mention the libraries in covering the ongoing battle between city and state officials. The headline news of the day on November 7 was, understandably, the German surrender that marked the end of World War I.

Allegheny County eventually tallied more than 60,000 cases of influenza that year as flare-ups continued into the winter.

If you’d like to learn more about the 1918 influenza epidemic, we recommend checking Overdrive for The Great Influenza by John H. Barry, Flu by Gina Colata or Influenza: The Hundred-Year Hunt to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History by Jeremy Brown. On Hoopla, you’ll find The Spanish Flu Epidemic and Its Influence on History by Jaime Breitnauer. To learn more about the flu’s direct impact on Pittsburgh, check out the article “Pittsburgh in the Great Epidemic of 1918” by Kenneth White, which appeared in Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine in July 1985, available via the Heinz History Center’s website.

Just as things eventually returned to normal for the library in 1918, they will this year, too. In the meantime, stay home, stay healthy, and go wash your hands!

*We believe these unsigned letters are from Dr. Leete as they were found in the Director’s Office records in the Carnegie Library’s archives, but the letters are unsigned since they were likely office copies of letters that sent to various parties.