Famously enacted in the 1939 classic, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the filibuster has evolved from the 18th-century word “filibustier” — referring to pirates who pillaged the Spanish colonies in the West Indies — to the present-day parliamentary procedure which aims to debate and/or prevent legislation within the Senate. Let’s take a look at how this four-syllable term came to be so important in American politics, and what changing or removing the filibuster could mean for Congress.

Filibuster Defined

The U.S. Senate defines filibuster as an “Informal term for any attempt to block or delay Senate action on a bill or other matter by debating it at length, by offering numerous procedural motions, or by any other delaying or obstructive actions.” (Source: U.S. Senate Glossary)

Debate is, and has always been, an important part of the Senate’s process. However, because a Senator is allowed to speak for as long as they wish, they can use filibustering as a tactic to block a measure by preventing it from coming to a vote. (Source: Congressional Research Service)

Any senator can trigger a filibuster. The most common formal step is for a senator to stand and say “I object” when fellow senators attempt to advance legislation (Source: The Equal Democracy Project). Today, the votes of 60 members of the Senate (equal to three-fifths majority) are required to terminate a filibuster and move to a vote. This is known as invoking cloture.

Filibuster Origins in the United States

According to the U.S. Senate, the tactic of using long speeches to delay legislative action can be traced back to the very first session of The Senate in 1789, though use of the term “filibuster” did not come about until the 1850s. Early filibusters led to demands for what is now called a “cloture,” which is a method for ending debate and bringing a question to a vote.

Senate Rule 22 was adopted in 1917, which allowed the Senate to invoke cloture with a two-thirds majority vote to put an end to a filibuster. This rule was first exercised in 1919 to an attempt to end a filibuster against the Treaty of Versailles. However, the Senate did not successfully overcome a filibuster until 1964 to pass a major civil rights bill. (Source: U.S. Senate)

Historical Examples of the Filibuster

There are several famous examples of the filibuster throughout history:

- On August 28, 1957, United States Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina began a filibuster, or extended speech, intended to stop the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. It began at 8:54 p.m. and lasted until 9:12 p.m. the following day, for a total length of 24 hours and 18 minutes. This made the filibuster the longest single-person filibuster in U.S. Senate history, a record that still stands today.

- In Frank Capra’s 1939 classic film, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, the fictional senator Jefferson Smith, played by Jimmy Stewart, tried to save a boys’ camp. In a real-life imitation of that Hollywood classic, New York senator Alfonse D’Amato tried to save a typewriter factory on October 5, 1992 by speaking for 15 hours and 14 minutes. If D’Amato had spoken for another 17 minutes, he would have broken the record Huey Long set in 1935 when he conducted the most notable filibuster in Senate history—the one that included his recipes for fried oysters and turnip green potlikker.

- The most recent filibuster took place in 2013, when Texas Senator, Ted Cruz, tried to block implementation of the Affordable Care Act by speaking for 21 hours, which consisted of reading “Green Eggs and Ham” by Dr. Seuss and sharing quotes from the reality show, “Duck Dynasty.”

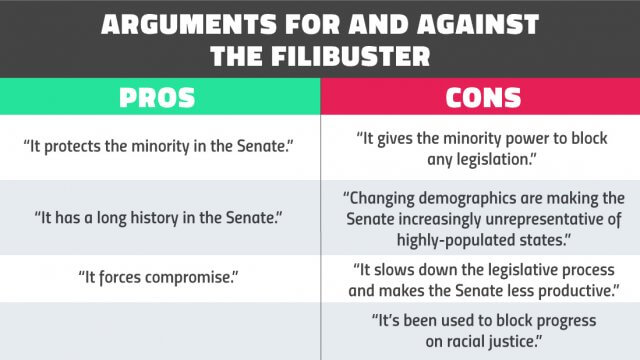

Why is the Filibuster Controversial?

Proponents of the filibuster contend that it protects the minority party from majority tyranny and encourages productive debate that stifles poor legislation. Critics counter that while this point may be theoretically salient, it flounders in practice under the weight of partisan gridlock and obstructionist realities. Rather than boosting fruitful debate to pass meaningful laws, skeptics assert that the filibuster is abused to yield the opposite result — suppressing debate and preventing popular bills that benefit Americans from seeing the light of the Senate floor. (Source: The Equal Democracy Project at HLS)

Without the filibuster, it would be easier for the majority party to pass legislation without opposition. Because Democrats currently control the majority of the House and Senate, eliminating the filibuster would likely mean a lot of laws authored by Democrats would pass. But, if the Republicans gain control of the Senate again, they too would have a much easier time enacting their agenda. (Source: RepresentUs)

Want to Learn More?

Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh is a strong proponent of supporting media literacy. “Media literacy“ is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate and create media messages in all their forms — from print to video to the internet and social media. (Source: EveryLibrary)

When consuming news updates about the current Senate Filibuster process, it’s recommended that you read both national and local news from various sides/viewpoints – read more about the importance of a balanced news diet here. You can also read side-by-side comparisons of an issue from sites like The Flip Side, which is ranked as “least biased” according to Media Bias/Fact Check.

Here are a few books from our Library catalog that showcase the pros and cons of the filibuster:

- Arenberg, Richard – Defending the Filibuster: The Soul of the Senate

- Jentleson, Adam – Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy